A Beginner's Guide

to Cassette Operation

with a Home Computer

by Samuel D. Pincus

You bought your TI-99/4A Home

Computer because the plug-in

Command Modules looked like a

quick and easy way to get started. You

played the games anti typed in the programs that you found in the Users

Reference Guide. Now comes the

moment of truth—What to do next?

The answer, fellow 99’ers, is easy:

Learn how to use a cassette tape recorder with your computer so that you

can begin to build up a program library

by recording and saving the many

excellent software programs that appear

printed in 99’er Magazine.

In order to get started you’ll need

a tape recorder cable, a cassette tape

recorder, and some good quality cassette

tapes. The cable assembly is specially

manufactured for Use with the Tl-99/4A

Home Computer (Dual Cassette Cable,

PHA2000) and should be available

from any TI retailer. Cables made for

other computers will not work with

your machine.

When it comes to locating a tape recorder, the matter isn’t as straight-forward: TI does.. not manufacture a

special tape recorder for use with their

computer and really doesn’t recommend

any one particular brand. There is a

good reason for this, because finding a

recorder, that provides satisfactory results is not as easy as you’d think.

To explain Why, I will have to give you

a quick background on how a computer

talks to a tape recorder and vice versa.

The first thing that you must realize

is that a computer is very, very dumb!

While your brain can understand things

like “yes,’ “no,” and “maybe,” a computer only understands “off” and “on.”

Everything, that a computer does is

based on the fact that it understands

only these two things.

What the Recorder Records

In order to do the wonderful things

your computer is capable of doing, the

“offs” and “ons” have to be arranged

into patterns that the computer can

use. This is true not only for numbers,

but for letters as well. For example,

if you type in the letter “A” on the

keyboard, your Tl-99/4A really sees

a pattern that looks like this: on-off

off-off-off-off-off-on. If we think of an

“off” as a zero and an “on" as a one,

the pattern looks like this: 10000001.

Remember that everything your TI-99/4A does is based on groups of

binary numbers like that. Each 1 or 0

is called a “bit” In addition, every

pattern of ones and zeros has its own

binary value.

Learning to count in binary is

beyond the scope of this article, but

there are a number of books or articles

around that can teach it to you. What

you should know for now is that each

letter and character has its own pattern

of zeros and ones and its own binary

value. In order to make it easier to

communicate with a computer, the

bits are grouped into groups of four.

Two groups of four bits is called a

“byte.” A byte can contain 256 differ-

ent combinations of bits (or values)

and has enough combinations to allow

a unique pattern for each letter, number

and character on your keyboard. For

example, the 65th possible pattern (a

byte value = 65) represents the letter

“A” in the ASCII character coding system used by the Tl-99/4A and most

computers. This means that 65 is the

ASCII value of the letter “A" That is

why the computer will give you back an

answer of 65 if you ask for the value of

ASC(”A”).

To make a word, the letters are

strung together (just like in English).

When you type in a word as part of a

TI BASIC program, the computer will

convert each letter in the word into a

byte and make sure that this particular

grouping of bytes makes sense. For

example, if you type in GOTO on the

keyboard, the computer will read that

as 7l 79 84 79.

In order to read data from a tape recorder, your computer will have to be

able to read in bytes of data. That

means that it will have to understand

“offs” and “ons” when listening to the

tape. Unfortunately, there is no such

thing as an “on” or an “off” to a tape

recorder. Even when it is absolutely

quiet to your ears, a tape contains some

amount of noise. So we can’t say that

no noise = “off” and noise “on"

Instead, we need another way for a

tape recorder to communicate an

“off” or “on” to the computer. This is

done by using two tones, each at a different frequency. The lower frequency

tone can then mean “off” and the

higher frequency tone will mean “on."

If your tape recorder cannot record or

playback the higher frequency, your

computer would only hear “offs"

Only these two tones are recognized

by the computer. If it “hears” any other

tone, your 99/4A will ignore it. Of

course, TI has added some tolerance to

the computer so that if it hears something almost like the “on” or “off”

tone, it will accept it as an “on” or

“off.” This means that for your 99/4A

to properly read data from a cassette

recorder, the tone must be both loud

enough (i.e., the volume set high enough)

to be heard and also be at the right

frequency.

Not all Recorders Are Equal

A principal law of physics states that

it takes more power to produce or

reproduce a high frequency than it

does to produce or reproduce a lower

frequency tone. If the volume is not

high enough during either recording or playback, your computer won’t

hear anything, or it might not be able to

hear the higher frequency tone. Alternately, it may hear all of the lower

frequency data tones that mean "off:

but only hear part of the higher frequency tones that means “on” In order

to help the TI-99/4A hear the high

frequency tones properly, the tone control knob on the recorder should be

set at or near the maximum level. Even

if this is done, some tape recorders

cannot handle the high frequency. If

your recorder doesn’t have a tone

control there’s a good chance it was

probably meant to handle only the frequencies of human speech and won’t be

mechanically able to handle the high

frequency tone at all.

Since it is possible that your recorder

cannot reproduce the high frequency

tones properly, your computer has to

be sure that it has read all the data. How

can it make sure that nothing was lost?

Your computer counts the number of

“ons” that it heard. After every so

many bytes, it expects to read a number

on the tape. This number tells the computer how many “ons” it should have

read. If the two numbers don’t match,

a “parity error” has occurred and the

computer will tell you that you have a

problem.

Now suppose that the volume is set

high enough to reproduce the high level

tones, but is up too high? Well too

much volume causes distortion in a tape

recorder. This distortion will mean that

some of the tones will not be heard

accurately by the computer at all. It’s

just like someone screamed in your ear.

You know something was said, but you

don’t know what it was.

Let’s recap what we just learned. In

order for your computer and the tape

recorder to communicate properly,

three things must happen:

First—the tape recorder has to be able

to handle both the high and low frequency tones and it must be capable of

reproducing them within a small range

of the frequency at which it was recorded. In order to record and playback

the higher frequency tone it is usually

necessary to have the tone control of

the tape recorder set at, or near maximum.

Second—the tape recorder must be capable of small volume adjustments so

that you can reach a condition where

the volume is loud enough to be heard

by the computer and yet low enough so

that there is no distortion.

Third—the tape recorder must be able

to record and playback the very quick

shifts in frequency (from “off” to

"on”) accurately so that no tone is

lost when being played back into the

computer.

A Remote Possibility

There is one additional problem that

may crop up even with tape recorders

that satisfy the above criteria: Almost

all cassette recorders have a remote

control jack which allows you to stop

the recorder by pressing a button or

switch located on the microphone.

Unfortunately since this jack is meant

to work with the manufacturer's own

microphone, there is no guarantee

that the jack is hooked up the same way

in each tape recorder. In fact, there is

a 50-50 chance that the tape recorder

model you buy or already own will not

be compatible with the system your

Tl-99/4A is expecting. This means that

the drive motor of your recorder might

not be capable of being turned on and

off automatically by the computer

when the plug on the TI cable is inserted

into the recorder’s control jack. Luckily,

if this is true for your recorder, 99’er-ware sells an inexpensive adapter (called

“TI-SETTE”) which is used between

your recorder and the TI cable. If you

don’t want to spend the money for this

adapter, you can get by without, by

manually starting and stopping the

tape, except if you intend to use

cassette files, in which case the auto-

matic operation is necessary.

The conclusion you can draw from

all this is that your Tl-99/4A requires

a tape recorder with specific attributes

in order to consistantly guarantee good

results. TI provides its owners with a

list of 2-6 tape recorder models that

work well with the 99/4A computer. If

you do not already own a recorder, I

strongly suggest that you buy one of the

recommended models. If you do have

a recorder, you can try it out before incurring the expense of purchasing a new

one.

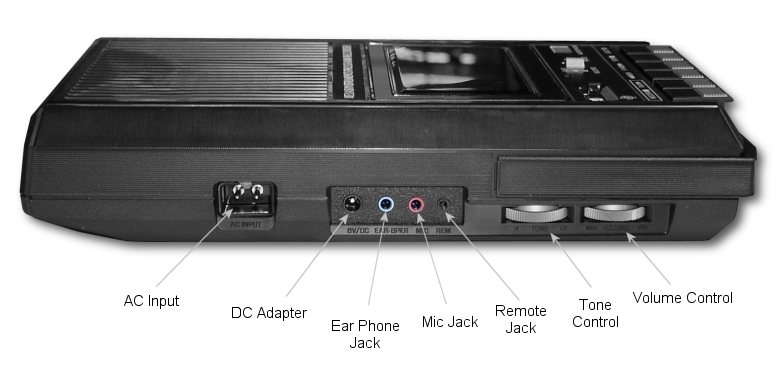

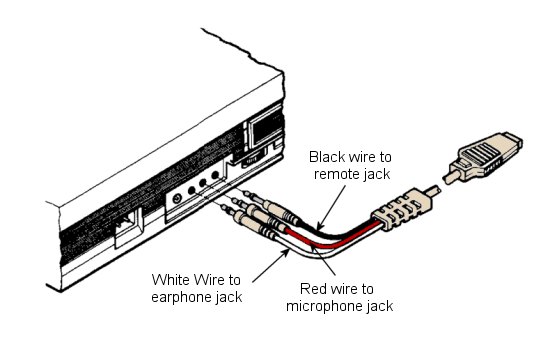

Plugging In!

Now that we have discussed why

some recorders won’t work at all or

won’t work with the remote control

jack plugged in, let’s get down to business. Shut off your machine and plug

the wide cable (with 9 holes in it) into

the hack of your computer. The other

end of the cable has two cords. One

cord has three plugs attached (labeled

plug #1), and the other (plug #2)

has only two. The tape recorder that

you connect to plug #1 will be called

“CS1” by the computer. If you are

lucky enough to have a second usable

tape recorder, you can hook up that

one to plug #2. It will he called “CS2”

by the computer. Just follow the installation instructions printed on the

card that came with the TI cassette

cable. If your tape recorder does not

have a remote control jack, just ignore

the instructions to insert the black

plug. Note that CS2 does not have a

playback plug. You can only record

on CS2.

Plug the tape recorder into an

electrical outlet and you are now ready

to check out your system. A battery

operated tape recorder is usually too

unreliable for recording and playing

back data for your computer because

of the fluctuations in speed and amplifier gain. Load a high quality

(remember we have to record those

high tones accurately!) C-10, C-15,

or C-30 blank tape into the tape recorder. The number part of the tape

code gives the number of minutes of

recording time available on both sides

of the tape. A C-10 tape has 5 minutes

of recording time on each side. You can

use a tape as long as a C-60, but never

anything longer. This is because longer

tapes are thinner, stretch more, and may

not maintain proper speed in the recorder. For this first test, make sure the

tape is completely blank. Turn on your

computer and get into TI BASIC. Key

in the following 4 line program:

100 PRINT “HELLO”

110 I=30

120 PRINT “MV VALUE IS”;I

130 END

Turn up the volume on your TV (or

monitor) by a few notches so that you

can hear a slight hum. Set the volume

control on your tape recorder mid-way

between the lowest and highest settings.

Set the tone control (if there is one) up

to maximum. Now type in SAVE CS1

and press the ENTER button. Follow

the instructions that the computer gives

you to rewind the tape and begin recording. When you press “record” on

your tape unit and then press the

ENTER button on the computer, the

tape should start moving.

If the tape doesn’t start moving, you

have a non-compatible remote control

jack. If this is the case, wait for the computer to get out of recording mode and

print the “VERIFY (Y/N)” message.

When it does, type in an “N". Now

remove the plug from the remote

control jack and begin the recording

process all over again (by typing SAVE

CS1 and pressing the ENTER button).

When you are told to record, you

should now see the tape moving.

Getting Adjusted

After a short pause, you will actually

hear your program being recorded onto

the tape. The recording consists of an

initial long phrase of a single tone,

followed by bursts of sound with a very

short pause between bursts. This initial

tone is used to tell the computer on

playback that data is coming. This tone

is recorded before each program and

each block of data (which we will talk

about later). When the recording is over,

you will get the verify message (see

above). Type in a “Y” (you don’t have

to press the ENTER button). Follow

the instructions about rewinding the

tape. When you play back the tape,

listen to the sounds that it is making.

Note that the volume is much louder

than when you recorded. If that initial

tone does not sound pure (it seems to

warble with the tone going higher and

lower), you are probably using a recorder that won’t work well consis-

tently. If the tone does seem pure,

you’re halfway home!

When the tape goes silent, the program has finished loading. You should

get a message that says either “DATA

OK” or “ERROR IN DATA”. If no

message prints, then the volume setting

was too low and your computer is still

waiting for the first recognizable byte of

data. It will eventually get tired of

waiting and give you a “NO DATA

FOUND” error. Just wait for this

message to appear, or shut off your

computer and start all over again.

If you got the “DATA OK” message,

you are home fre& Relax and go on to

the next paragraph. If you were unlucky

enough to get a “NO DATA FOUND”

error, turn up the volume one notch. If

you got the “ERROR IN DATA” message, you probably had the volume too

high. Lower the volume one notch. Write

down the latest notch on a piece of

paper. In either case, respond to the

computer question by entering an R to

re-record. The computer will guide you

in another recording session. Keep repeating the process until you can’t

change the volume any further, or the

“DATA OK” message appears, or the

error message has changed (i.e., from

“NO DATA FOUND” to “ERROR

IN DATA”). If you can’t change the

volume any further, your recorder

just isn’t good enough. Don’t aggravate

yourself, any longer, go out and buy

one from the list. If the DATA OK message has appeared you are in good

shape. If the message has changed, back

off your last change by half a notch.

For example, if moving the control

from 6 to 7 made the “ERROR IN

DATA” message appear, try the recording process again at 6 1/2. If that doesn’t

work, try it at 1/4 notch intervals. If that

doesn’t work, forget it. Buy a different

recorder.

After you get the “DATA OK”

message, mark the volume setting in

some way. I usually dip a toothpick in

white paint (a light nail polish will also

work) and dab a line on both the recorder and the control so that I can

easily see that the volume setting is

correct. You now have a functioning

cassette tape system and are ready for

bigger and better things!

Better Safe than Sorry

When you entered the SAVE CS1

command, you told the computer to

copy the bytes that represented your

program inside the computer onto a

tape. The entire program is saved each

time. Your program is still in the computer, however. If you agree to verify

your tape, TI BASIC will read in the

tape and compare it in a byte-for-byte

manner with the program still residing

in memory. Unless the two match

perfectly, your 99/4A will issue a

warning that you have a bad tape.

ALWAYS VERIFY ANY SAVEs BEFORE ENDING A PROGRAMMING

SESSION!

The tape version of the program is

saved in a “machine image" format that

is meaningful only to TI BASIC. You

cannot, however, write a Tl BASIC program that will read this tape. The only

way to get your program back into the

99/4A is via the OLD CS1 command.

This will load the program back into

the machine. Anything that may have

been in the computer before the OLD

CS1 will be lost. By the way, you can

SAVE CS2 (if you have a recorder

hooked up to cable #2) and then read

in the tape by entering OLD CS1. Of

course, you have to move the tape over

to the recorder attached to cable #1

first!

The instructions built into the TI-99/4A whenever you enter the SAVE

CS1 or OLD CS1 command assume that

you have only one program per side of

tape. In reality, you can save more than

one program per side. A long program

will require about 3-4 minutes of recording time. This means that it is

possible to save about 4-5 programs on each

side of a C-30 tape. If your recorder has

a tape counter, just keep track of where

the next free space on the tape is located. Then, when the computer tells

you to rewind the tape, just fast-forward

to that next free spot on the tape instead. Just make sure to keep a log of

what programs are recorded on a tape

and where they are located. If you

don’t want to be bothered by this, and

want maximum, reliability, it is better to

use C-10 cassettes and record only one

program per side.

A cassette tape recorder will usually

have the ability to record a new program directly over an old one. It is

good to get into the habit of completely

erasing a tape, however, when you no

longer need it. This ensures the best

possible recording the next time you

use the tape.

Filing Data

The cassette recorder also makes a

handy data storage device for use in

your computer programs. Suppose that

you have written a program to keep

track of the bowling scores and figure

out the handicap of each member of

your bowling league. You don’t want to

re-enter this information each time you

run your program. What you need is

a way of saving the data when you are

through with it so that it can be read

in the next time around. Some people

do this by coding in the information in

DATA statements each time before

SAVEing the program. A better way of

doing this is to write out a small “file”

of data onto a tape. Your program can

then read in this data the next time it

runs. TI BASIC has an easy way of

doing this by using the INPUT # and

PRINT # statements.

Before you can read or create a file,

you must tell the computer a little

about your file. This is done by the

OPEN statement. Your reference

manual does a pretty good job of explaining this statement, so I’ll just go

over the parts specifically dealing with

cassette tape files.

Unlike the SAVE command which

writes out your entire program as a

large “chunk” of data, BASIC data

files can only handle small chunks

of data, called “records,” at a time.

Each file can contain 1 or more records.

All cassette records in a file must be of

the same size. They can all be 64 bytes

(characters) long, 128 bytes long, or

they can all be 192 bytes long. You can

specify other lengths as part of the

OPEN statement, but TI BASIC will

boost the number up to either 64, 128

or 192. If a record you want to write

is shorter than the length that you

specify, TI BASIC will add enough

blanks at the end of the record to make

it the right length.

Each record can contain as much

data as you can fit in that size record.

When you have a statement that says

PRINT # and ends with a semi-colon,

BASIC will add that data to the record,

but will not write anything out to the

tape. When BASIC sees a statement

with PRINT # that doesn’t end with

a semi-colon, it will write out everything in a record (including this last

piece of data) to the tape. When the

record is written to tape, it is preceeded

by the same steady high-pitch tone that

starts off a SAVE. That means that

BASIC uses a lot of tape to write a

single record. In fact, if you use records

that are only 64 bytes long, it is possible

that more room is spent on the tape for

the start tone then is used to record the

data! Remember that more room on

the tape means slower reading by the

computer. That’s why I usually use 192

byte records and try to fit as much data

as possible into each record. Doing this

will cut down on the number of records

written to tape, and make the program

run faster.

Since TI BASIC only writes to

tape when you tell it to, the computer

must have total control of the cassette

recorder so that it can start and stop the

recorder as needed. This means that the

black remote-control plug must be in-

serted (and functional!). If your remote

jack is notcompatible with the Tl-99/4A,

you will not be able to use the recorder for saving and reading data under

program control. This is where the

TI-SETTE Adaptor, listed at the end

of this article, can help.

You can store in two different

formats. DISPLAY format means the

data is saved just the way it would look

in a DATA statement. INTERNAL

format saves the data in the same way

that the computer stores the information internally. Numbers require 8

characters (bytes). Strings (i.e., names)

require 1 byte (for the length) plus the

data itself. I usually save my data in

INTERNAL format so that I know the

length needed for numbers no matter

how big or small they are.

The BASICs of Record Keeping

Let’s write a part of a program that

will save each bowler’s name, his pin

average and his handicap. Pretend that

we have 60 bowlers in our league. If we

restrict each bowler’s name to a maximum of 47 characters, we will need a

total of 64 bytes per bowler (47 bytes + 1 48 for the name + 8 for the average + 8 for the handicap 64). We can

therefore fit the data for 3 bowlers into

one 192 byte record.

090 REM ROOM FOR 60 BOWLERS NAMES, AVERAGES, HANDICAPS

100 DIMENSION B_NAME(60),B_AVG(60),B_HANDI(60)

995 REM OPEN THE FILE FOR OUTPUT

1000 OPEN #1:”CS1”,OUTPUT,INTERNAL,SEQUENTIAL,FIXED 192

1010 X=l

1020 FOR 1=1 TO 60

1025 REM SEE IF RECORD IS FULL

1030 IF X=3 THEN 1100

1040 X=X+l

1050 REM ADD TO RECORD— BUT DONT WRITE IT OUT

1060 PRINT #1 :B_NAME(I) B_AVG(f)B_HANDI(I);

1070 GOTO 1120

1090 REM ADD TO RECORD AND WRITE IT OUT!

1100 PRINT #1 :B_NAME(I);B_AVG(I);B_HANDI(I)

1110 X=1

1120 NEXT I

1130 CLOSE #1

If you have filled up a record by the time

the program hits the CLOSE statement,

TI BASIC will fill the record with

blanks and write it out. You do not

have to worry about writing out a last

record that is partially full. Just remember to always code in a CLOSE

statement. To read the data file into your

program, you need code that almost

duplicates the write code.

195 REM OPEN THE FILE FOR INPUT

200 OPEN #1:”CS1”,INPIUT,INTERNAL,SEQUENTIAL,FIXED 192

210 X=1

220 FOR 1=1 TO 60

230 REM SEE IF RECORD IS FULL

240 IF X=3 THEN 300

250 X=X+1

260 REM READ RECORD-- BUT DON’T READ TAPE

270 INPUT #1 :B_NAME(I);B_AVG(I);B_HANDI(I)

280 GOTO 320

290 REM READ RECORD AND GET NEXT TAPE

300 INPUT #1 :B_NAME(I);B_AVG(I);B_HANDI(I)

310 X=1

320 NEXT I

330 CLOSE #1

Note that statement 300 reads in the

last piece of the record and tell TI

BASIC to read in a new tape record

the next time it sees a READ #1

statement.

When your program hits the OPEN

statements, it will issue commands

about rewinding the tape and pressing

ENTER. Just before it reads the first

record, the screen will scroll up one line

to indicate that it has begun processing

the tape.

I have often been asked why TI

provides the CS2 plug. I have to admit

that most manufacturers do not provide

dual cassette support. It is useful if

you must process more data in your

program than the computer can handle

inside its memory. You would need two

recorders hooked up, and would read

in as much data as possible (for example,

as file #1) on CS1, then do whatever

you have to, and finally write the updated data out on CS2 (as a different file

number). You would then go back and

read in the next batch of data from

CS1, update it, and write it out. You

repeat this until there is no more data

on CS1. This allows a small computer

to handle very large files.

At this point you should have the

basic knowledge for choosing a cassette

recorder, and getting it to work with

your computer. Keep in mind that

tape storage transforms your Home

Computer into a very powerful and

versatile machine. And once you get

familiar with the few simple procedures

and precautions, each occasion of saving

and loading programs and data files will

become second nature, one might

even say, “filled with memories . ."

|