1958 -- Integrated circuit invented by Jack Kilby

|

(View Video 6 1/2 min, Windows Media Player)

|

During the summer of 1958, TI shut down for the annual two-week, company-wide mass vacation. As a new employee,

Jack Kilby had not yet accrued vacation time, so he stayed on the job and began looking for a viable alternative to

the micro-module program, a miniaturization method for circuits. While studying the problem, he decided the only

product a semiconductor house could make cost-effectively was a semiconductor. Perhaps other circuit components should

be made from the same material as the semiconductors.

Kilby drew up a few sketches and showed them to his manager, Willis Adcock, as soon as the vacation period had ended.

Adcock was optimistic, but cautious, about the new idea. He suggested that Kilby try building a working circuit,

utilizing components made from silicon. With Adcock's orders in hand, Kilby carried his sketches to the lab and asked

the technicians to fabricate some silicon resistors and capacitors. He wired these parts into a transistor flip-flop

circuit and demonstrated the working device to Adcock on August 28. Kilby was given the go-ahead to continue his project,

and when he designed the next circuit, he integrated all the individual components onto a single bar of

semiconductor material. He sketched in his notebook the complete circuit of a phase-shift oscillator on a bar

of germanium.

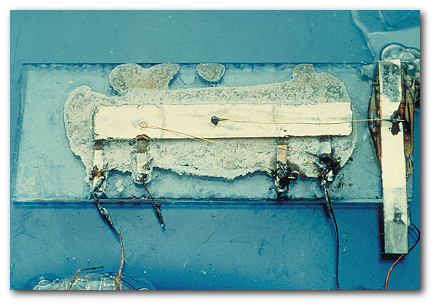

Within two weeks, the first three oscillators were completed and ready to test. What TI managers saw on that

historic day of September 12, 1958, was a tiny bar of germanium, measuring 7/16-x1/16-inches, with protruding wires,

glued to a glass slide. It was a rough device by anyone's standards. But when Kilby applied the voltage, an unending

sine wave undulated across the oscilloscope screen.

It worked just as Kilby thought it would. He had solved one of the most perplexing problems associated with

miniaturization. Once his invention was accepted, it would revolutionize the electronics industry. As Kilby said,

“What we didn't realize then was that the integrated circuit would reduce the cost of electronic functions by a

factor of a million to one. Nothing had ever done that for anything before.”

Jack Kilby's first working integrated circuit, tested on September 12,

1958, consisting of a transistor and other components on a sliver of germanium, 7/16 x 1/16 inches, which

revolutionized the electronics industry. Kilby often remarked that if he'd known he'd be showing the first

working integrated circuit for the next 40-plus years, he would have "prettied it up a little."

|

|

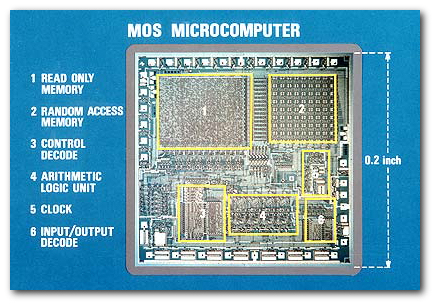

1974 -- TMS1000 single-chip microcomputer released

In 1974, TI introduced the TMS 1000, a general-purpose single-chip microcomputer that gave TI the lead in the market

for 4-bit consumer, automotive, and industrial applications.

Reliability was enhanced by single-chip construction that cut component counts as much as 75 percent – which helped

hold total system costs down. TI's total support went further, and included customer training courses, software

development and applications engineering staff, and field application specialists. The microcomputer was used in

applications such as communication systems, electronic games, vending machines and cash registers, terminals and

peripherals, industrial controls, gas pumps, and credit card verifiers.

|

TI highlighted the TMS 1000, the first microcomputer on a chip,

in its 1975 First Quarter and Stockholders Meeting Report.

|

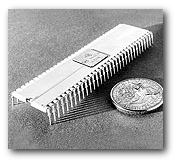

1975 -- TMS9900 16-bit microprocessor chip released

By 1975, TI was ready to disclose its 9900/990 software-compatible family of 16-bit microprocessors and minicomputers –

the heart of its strategy for vertical integration. This strategy was the outgrowth of a task force put together to

look at next-generation computers. The TMS9900 was the industry's first 16-bit microprocessor. The 9900/990 family

was designed with an innovative memory-to-memory architecture.

These products were at the heart of an innovative strategy TI hoped would create an entirely new business. In 1976,

the company made it official — distributed computing would be one of TI's three major thrusts. In 1976, the TI 990

became the first in a growing family of minicomputers based on software compatibility with TI's 16-bit microprocessor.

Evolution of the 9900 family continued with the 9995 and 99000 microprocessors but came to an end in 1982, when

it became clear that TI's future microprocessor success would require differentiation from what other companies

were doing. A newly formed team embraced a concept called function-to-function architecture that emphasized

microprocessors tailored for particular system functions. Digital signal processing, local area networks,

floating point arithmetic, and graphics were selected as areas of focus.

In 1975, TI introduced the industry’s first microprocessor that used software language compatible with a minicomputer

family, the 16-bit 9900, pictured here next to a 25-cent piece for size comparison.

|

|

1978 -- Single-chip speech synthesizer debuts in TI Speak & Spell™ learning aid

An outgrowth of TI's research in the area of synthetic speech, the Speak & Spell™ educational product was designed

to help children age seven and older learn how to spell and pronounce more than 200 commonly misspelled words.

It began in 1976 as a three-month feasibility study with a $25,000 budget. Four TIers worked on the project in its

early stages: Paul Breedlove, Richard Wiggins, Larry Brantingham, and Gene Frantz. The concept for Speak & Spell

grew out of Breedlove's brainstorming for products that might demonstrate the capabilities of bubble memory

(a TI research project). He concluded that speech data took a lot of memory and would be a good application.

The talking learning aid used an entirely new concept in speech recognition. Unlike tape recorders and pull-string

photograph records used in many “speaking” toys at the time, TI's Solid State Speech circuitry had no moving parts.

When it was told to say something it drew a word from memory, processed it through an integrated circuit model of a

human vocal tract and then spoke electronically.

It marked the first time the human vocal tract had been electronically duplicated on a single chip of silicon.

The consumer product was introduced at the Summer Consumer Electronics Shows in June 1978.

The success of Speak & Spell extended TI's thrust in educational products to Speak & Math™, Speak & Read™,

Speak & Music™, and a whole collection of speaking children's toys. Speak & Spell went around the world –

in several languages.

Although it was introduced more than 25 years ago, the basic learning principles and design concepts behind Speak

& Spell remain the standard for educational toys. Speech synthesis and voice recognition applications are pervasive

today – ranging from telephone applications for checking airline schedules, to voice-assisted navigation systems in

automobiles, computers for the blind, and security applications.

|

The Speak & Spell™ learning aid functioned much like a parent preparing a student for a spelling quiz.

It would say the word, allow the pressing of keys labeled with the alphabet to spell out the word, then

report on the result of the effort.

|

This technolgy would later be incorperated into the Speech Synthsizer which would allow speech on the TI-99's.

|

|

1979 -- TI 99/4 Home Computer introduced

|

|

(View Video 20 sec, Windows Media Player)

|

In the early 1970s, Chairman Pat Haggerty and his management team had many strategic discussions about the potential

for low-cost semiconductor functions to make possible a computer for the home with implications for commercial,

educational and recreational uses. These discussions led to a home computer project. After the commercial success of

TI calculators, the home computer seemed the logical next step. The home computer became TI’s biggest bet in the quest

for vertical integration, but the venture proved to be a dry hole. The huge negative impact on TI’s financial health

might have sunk the company, except for its strong balance sheet, diversified position, and determination to learn

from the experience.

Visitors to the Consumer Electronics Show in June 1979 were able to see TI’s 99/4 Home Computer for themselves,

confirming rumors that had circulated for months. Its central processor was TI’s 16-bit TMS9900 microprocessor,

designed to give it a leg up on other 8-bit home computers in the market. Equipped with a 13-inch video color

monitor, it was designed to use plastic plug-in modules of read-only memory, which contained programs such as games,

personal finance, and educational software. The reaction was generally favorable, although some were surprised at the

high price tag of $1,150.

Feedback from the market indicated the need for more software titles, a better keyboard, more peripherals and a lower

price. A redesigned home computer, the 99/4A, was introduced in June 1981, priced at $525.

A major marketing program was created to build sales. The primary channel of distribution was shifted from computer

stores to high-volume retail outlets. A team of more than 2,000 school teachers was recruited and trained to demonstrate

the product in the stores. A creative TV ad campaign was developed using Bill Cosby as spokesman. The International

99/4A Users Group became an important source of additions to the rapidly growing library of software. As TI gained

market share and volume, the 99/4A price at retail dropped to $299 to meet increasing pressures from competitors.

In April 1982, TI reported it had a major position in the emerging home market, with more than 5,000 retail outlets

carrying or committed to carry the 99/4A. Although the market had been slow to develop, it began to expand rapidly

in 1982, and production was increased.

By August 1982, 99/4A sales were growing rapidly, but the success of the home computer was causing stiff price

competition. TI decided to offer a $100 rebate.

By early 1983, TI had shipped the one millionth 99/4A home computer. The distribution network had expanded to

20,000 retail outlets worldwide. More than 2,000 software packages, developed largely by third-party authors,

were now available for the computer, and agreements were in place with several education and game publishers.

Then, disaster struck. It was discovered that under certain circumstances, a person might receive an electrical

shock from the computer’s power supply, although no user had yet experienced such a problem. TI armed itself with

the facts, reported them to the safety regulatory authorities, and made the decision to temporarily shutdown the

99/4A program while new power supplies were manufactured and shipped to TI. All 99/4A retail inventories and

customer returns were reworked and returned. TI accrued $50 million as the estimated cost to solve the problem.

Even more damaging was TI’s two-month absence from the retail marketplace.

A rescue team of seasoned TI managers was formed and sent to Lubbock, Texas, headquarters and manufacturing site

for the home computer. This team along with the Lubbock home computer team mounted an intensive effort to recover

from the transformer problem, restore the sales momentum at retail, adjust production and inventories and to reduce

costs, but they faced a tough situation.

|

TI introduced the TI 99/4A home computer in 1981, as a redesign to the 99/4 computer.

It is pictured here with peripherals, plastic plug-in software modules (lower right),

and color TV monitor. In 1981, this was state-of-the-art graphics in home computer displays,

made possible by TI's 16-bit 9900 microprocessor.

|

1983 -- Exit from home computer market announced

On October 28, 1983, TI announced it was withdrawing from the home computer market. When the smoke cleared and results

were in for the year, TI reported that the total segment losses from the home computer were approximately $680 million,

including operating losses, write-downs, write-offs, and other accruals associated with the shut down.

The withdrawal from the market hurt TI’s finances, but the damage to its psyche and reputation was just as painful.

Many worried that TI’s profitable and successful calculator and learning aid business would be adversely affected.

What TI did next, however, was a testament to the character of the company: TI decided to continue support for 99/4A

users during the withdrawal, to honor warranties, and to help dealers with their inventories. It was a big price to pay,

but TI thought it was the right thing to do. TI’s calculator and learning aids business thrived.

Although TI’s shutdown of the 99/4A Home Computer was the one most widely reported, over the next year or so, most of the

major home computer manufacturers quietly left the market after experiencing their own disappointments. Many years later,

an array of quite different digital products emerged tailored to serve specific sub-segments of the home market, including

games, education, communication, and small business/home office applications. TI continues to provide semiconductor

solutions to its customers in many of these applications – with a valuable perspective earned from the painful lessons

of the home computer market experience.

All information on this page "Courtesy of Texas Instruments"

© Copyright 1996-2006 Texas Instruments Incorporated. All rights reserved.

|

|